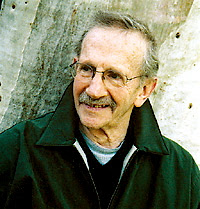

On this date in 1928 Philip Levine was born in Detroit, Michigan. His upbringing among working-class immigrants and African Americans living under the rule of continuing racism forever shaped Levine’s view of the world. The family figures he knew as a boy in the urban landscape of Detroit and the young men he met as a worker in its automobile factories have been ever-present as personages in his poetry. Even today, his poems often read as elegant yet plain-spoken elegies giving tribute to those who were battered and scarred, who felt chronic pain suffered during everyday battles, or those outcasts and artists (particularly writers and jazz musicians) who lived on the edges of society, men and women he once knew and to whom he now has given voice, again and again.

On this date in 1928 Philip Levine was born in Detroit, Michigan. His upbringing among working-class immigrants and African Americans living under the rule of continuing racism forever shaped Levine’s view of the world. The family figures he knew as a boy in the urban landscape of Detroit and the young men he met as a worker in its automobile factories have been ever-present as personages in his poetry. Even today, his poems often read as elegant yet plain-spoken elegies giving tribute to those who were battered and scarred, who felt chronic pain suffered during everyday battles, or those outcasts and artists (particularly writers and jazz musicians) who lived on the edges of society, men and women he once knew and to whom he now has given voice, again and again.As I mentioned in my review of Breath (2004) that appeared in “One Poet’s Notes” last January: “Perhaps no other contemporary poet has exhibited as large a cast of characters in his or her poetry as Philip Levine has in his heartfelt elegiac lyrics concerning personal relations, as well as in the eloquent emotional reflections on historical figures or cultural icons whose influence may have helped mold Levine’s own heart and certainly aided in shaping his art.”

I also reviewed his previous collection, The Mercy (1999), in the initial issue of Valparaiso Poetry Review (Fall/Winter 1999-2000). As I noted then, Levine’s most recent collections have displayed a mature voice even more concerned with mortality and a need to preserve memories: “Early in his career, Levine's poetry was often characterized as very angry, and that anger provided much of the energy fueling many of his best poems. But that rage evident at an earlier age and in a large share of his poetry, although not gone altogether, has given way to some extent in recent years, especially in his three latest collections, to an even more thoughtful and reflective poetry exhibiting an even greater generosity of spirit.”

With the poems in Breath, Levine continued in this vein, as I observed: “In the last two decades readers may have detected a mellowing voice in many of Philip Levine’s poems, which has resulted in a strengthening rather than a weakening of the poetry. The language one finds in his recent collections appears more open to a greater range of sentiments and to possibilities of extending forth moments holding tender emotions without slipping into sentimentality.”

The author of nearly twenty books of poetry, Levine is one of our most honored contemporary American poets. The Simple Truth (1994) won the Pulitzer Prize; What Work Is (1991) won the National Book Award; Ashes: Poems New and Old (1979), won both the National Book Critics Circle Award and the first American Book Award for Poetry; 7 Years From Somewhere (1979) won the National Book Critics Circle Award; and The Names of the Lost (1975) won the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize. In addition, Levine has received the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize from Poetry, the Frank O'Hara Prize, and two Guggenheim Foundation fellowships.

Today, on Philip Levine’s 80th birthday, readers can celebrate and salute the poet by listening to an audiotape of Levine reading “Messieur Degas Teaches Art and Science at Durfee Intermediate School, Detroit 1942” on the Academy of American Poets website or by viewing a wonderful film clip on YouTube of Levine reading poetry at a fundraiser for KPFA in Berkeley. Audio presentations of an interview with the poet and a full reading by Levine also are available at the Lannan Foundation.

Perhaps the final section of the five parts in “Dust,” a poem appearing in Breath, would provide a fine touch on this January birthday as well:

On a TV spectacular the cosmos

spins like a snow shower in a light show

of heavenly bodies. I’m reminded of Dust Bowl

photographs on Life magazine: a farmer

and his woman run toward shelter while the earth

they tore some living from rises against them

with all its plenitude. The man and woman

are not driven from their garden in shame

as in a painting, their mouths broken with moans.

These two borrow a Ford with bad tires and worse spares;

they have themselves and three kids to feed, and so

like the wind they head west where perhaps the land

has settled down, decided to be merely

the land they’ll someday take up living in.

Even the atom may be largely empty space,

the TV says. Einstein and Niels Bohr quarrel

for days and resolve nothing. Tonight my wife

holds a glass of black Catalan wine up

to the candlelight and drinks to my New Year

and I to hers, acts as good as any

to stall our time from whirling into dust.

[Important reminder: With the start of January, the Valparaiso Poetry Review Facebook group page has been instituted to allow readers an opportunity to quickly keep up with Valparaiso Poetry Review issue releases and news updates about the journal, as well as those book reviews and topics on contemporary poetry regularly presented here on “One Poet’s Notes.” The VPR Facebook group is global and open to everyone, and I invite all readers of Valparaiso Poetry Review or “One Poet’s Notes” to visit the page, where I request you add your name as a member.]

4 comments:

There is no University of Berkeley -- you are confusing this with the University of California at Berkeley, which is commonly referred to as just Berkeley by the media (save for the sports pages, which invariably label it Cal). But this is a fundraiser for KPFA radio, not a reading at the school.

Thanks, Ron. I have made the correction.

I was educated on the poems of Philip Levine because I studied under his student, the late and great Larry Levis. And my students were educated on the poems of Larry Levis.

Happy birthday, Mr. Levine! And thank you for your poetry and your teaching -- you see now just how far it reaches and will continue to reach.

Debra Di Blasi

thanks this blog very nice

http://improvesearchresults.blogspot.com/

improve search results

Post a Comment